Day 6: Thursday, March 7th

My final full day with the Betty Davis crew in Japan had arrived. With Matt Sullivan (founder/co-owner of Light in the Attic) and our translator Greg Gouty (the head of LITA international sales) busy with more record label meetings, John Ballon and I set out to enjoy our last bit of adventure in the place that Betty often called her “spiritual home.”

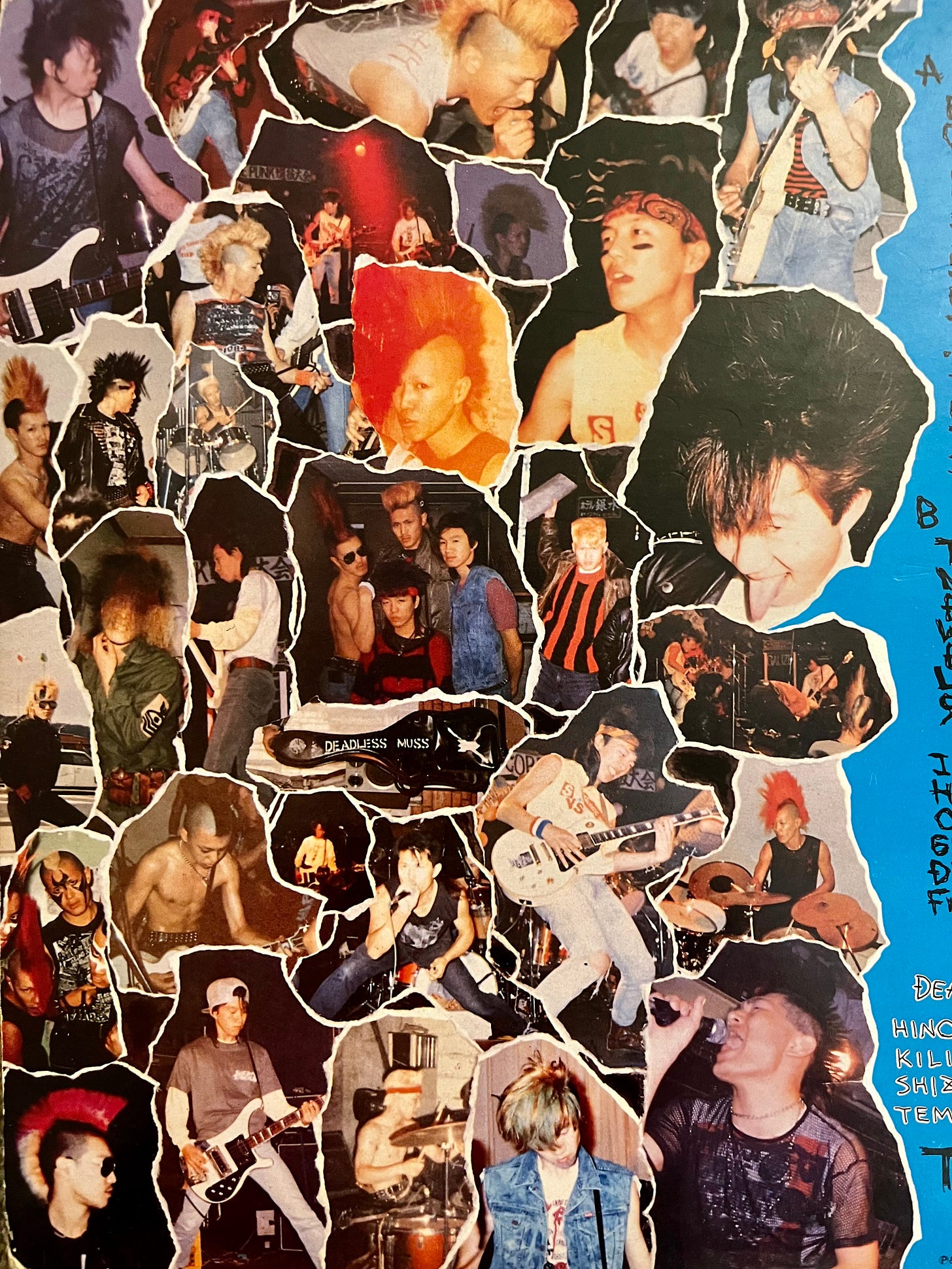

I had only one Betty-related item of business on my agenda for the day, which was meeting with Alex Easley, an African American musician who’s been living in Japan since the 1970s. It was Easley–a friend of Betty’s younger brother who grew up with them in their hometown of Homestead, PA–who offered Betty her first point of contact when she moved to Japan at the end of her performing career. We weren’t due to meet until the late afternoon, which meant that John and I had some time on our hands for additional record shopping (shocking, I know) in some of Tokyo’s glorious music stores. Our first stop was back to the multi-story Disk Union in Shibuya. Having had already perused their dance/club, hip hop, and soul/R&B collections a few days ago, I went directly to the rock and punk floor so I could hunt down some Japanese hardcore for my partner. I selected a few titles, including a 1988 album from Deadless Muss called 5 Years Imprisonment, released on Selfish Records.

A deep connoisseur of jazz, John brought us next to Discland Jaro, a basement record shop founded in 1973 that’s known for both its serious collection of jazz titles as well as its often ambiguous operating hours, as one can glean from various stories posted online by frustrated jazz shoppers. Unfortunately, we also found the revered establishment closed for business when we arrived at the location.

We needed something to heal from our failed digging expedition, and we figured that ramen would be a comforting cure for vinyl dejection. After reaching the bottom of the most delicious bowls of ramen we’d ever had, the temporary setback was behind us (though we still went back after lunch to see if the store was open; it was not).

With several hours to spare before my meeting with Alex Easley, we decided to visit the Tokyo National Museum, which is the country’s oldest national museum and also houses its largest public displays of art. Traversing the museum was truly a remarkable experience, particularly for someone who hails from a relatively young country like the US. Viewing their holdings of artifacts and artwork–some which date over a thousand years old–was awe-inspiring. We were especially taken with the 8th century roof tiles of Kokubunji from the Nara period, the 6th century tomb sculptures found in Isesaki City from the Kofun period, and the 12th century dharma wheels excavated from an Edo Castle.

We eventually entered a long hall that housed an extraordinary collection of kimonos. I was particularly drawn to a 19th century green kimono from the Edo period that was decorated with pines, peonies, autumn leaves, peacocks, and flowing water. Betty would have been deeply moved by the exquisite kimono designs, and both John and I wished more than anything that we could show her our pictures–something we’d both been doing for years to share the various places we visited with Betty, who did not travel in her later years and was highly selective about the company she kept.

Over the course of six days, it felt like we got a solid glimpse into Tokyo’s incomparable food scene and nightlife as well its unique culture of listening cafés and the seriousness of its record stores. Our impromptu visit to Tokyo National Museum provided us with another essential experience to better appreciate the East Asian archipelago. The attention to beauty and detail for which Japanese culture is known became evident to us in both its modern expressions–such as Michelin-star omakase meals and the white-gloved handling of classical music records–and in its ancient artifacts, its national collections, and via the sacred shrines we felt honored to visit near the majesty of Mount Fuji. Being immersed in such a distinctive blend of the old and the new, even for such a short stint, had proved to be wildly invigorating and inspiring.

In my conversations with Betty over the years, it was easy to surmise how much she loved Japan and how deeply her experience there shaped the final decades of her life following her return to the States. But after traveling there myself, with Betty’s soundtrack and her former bandmates, friends, and lovers guiding our way, it was clearer to me why her time in this country–removed from her unique baggage tied to American culture–was such a powerful source of comfort and healing for her during some of the most difficult times of her life.

…

Unlike the other individuals I spoke with in Japan, Alex Easley knew Betty before she arrived in 1983. He also knew her family and the joys and strains that all families like theirs endured. To Mr. Easley, as he preferred to be called, Betty Davis was always his best friend’s big sister. But he is also someone whom Betty would reconnect with during key moments in her life and career.

When Mr. Easley and Betty’s younger brother graduated from high school, they visited her in New York City when she was a Greenwich Village “it” girl who was DJing and MCing her own club in Harlem called The Cellar. After his initial visit with her, Mr. Easley decided to give the Big Apple a go and moved there himself. Betty hooked him up with a retail job at the up-and-coming Betsey Johnson boutique shop, Betsey Bunky Nini, that opened in 1969. A few years later, he visited Betty in the Bay Area while she was recording her debut album on Just Sunshine Records in 1972. Mr. Easley continued to stay close to Betty’s brother and followed her career throughout the 1970s.

Now a devout Christian who curates his own spin on “gospel weddings” in Japan, Mr. Easley requested that we meet alone, in the lobby of my hotel, and that I not record our conversation. He was extremely cordial in his introduction and made himself clear that because Betty is no longer living, he didn’t feel comfortable talking about her. I proceeded to spend the next forty-five minutes or so navigating this unexpected obstacle. I began by explaining who I was and how my travels to Japan grew out of a six-year relationship with Betty at the end of her life, which resulted in me helping to carry out her final wishes at Mount Fuji.

It was clear that Mr. Easley’s intention to not divulge much about Betty’s time in Japan was out of respect for Betty and her family. There was no way for him to know how much I already knew about Betty’s history and, more specifically, the events that transpired prior to her stint in Japan. After the death of her father in 1979, the same year her final studio album Crashin’ From Passion was shelved, she moved back to Homestead and lived with her mother for a short period of time. Those years proved incredibly difficult for Betty, who was grieving not only the loss of her father but also her standing in the music industry. Once I shared my intimate knowledge of Betty’s past, Mr. Easley was at least willing to discuss some logistical details about how she came to briefly stay with him in Japan, following her brother’s suggestion that she connect with him to make one final push in her then stagnant career.

Mr. Easley had initially come to Japan through Itsuro Shimoda, Betty’s “great love” who I met with just three days prior. I told Mr. Easley of our meeting and played him videos that I took of him performing. He was overjoyed to see his old friend with a guitar in front of an audience. Finally, some puzzle pieces were beginning to fit together.

Mr. Easley met Shimoda in New York City while the Japanese musician was working on the 1970 musical, Golden Bat, presented by a theatre troupe called the Tokyo Kid Brothers. The rock musical, for which Shimoda wrote the music, was an Off-Broadway hit. In a June 27th, 1970 review, The New York Times referred to Golden Bat as “a tribal musical in the tradition of Hair.”

Shimoda returned to Japan in the early 1970s to begin his popular recording career as a psychedelic-folk musician. Then, by invitation, Mr. Easley joined him in Tokyo and began singing in Shimoda’s musical group, Shimonsai. Mr. Easley fondly recalled that first year in Japan making new friends and connections in the music industry, citing the Japanese rock band, Flower Travellin’ Band, as an important musical and social channel.

Once Betty made her travel arrangements to Japan, which were supported by her brother, it was Mr. Easley who picked her up from the airport upon her arrival in the country. She initially roomed with him for a short period of time until she moved into a YWCA on her own. It was Mr. Easley who introduced Betty to Shimoda. And, as it turns out, it was also Mr. Easley who introduced Betty to Mr. Nishi at The Crocodile Club, where he had been gigging regularly. Mr. Nishi was aware that the Arakawa Band was looking for a new female vocalist to work with, and the rest fell into place.

While Mr. Easley respectfully declined to offer any impressions or opinions about Betty’s time in Japan, he had successfully connected some dots for me, and I was incredibly grateful. I gifted him with all of Betty’s reissued CDs (a gesture I picked up from Matt during our previous meetings) and thanked him for his time. He left the hotel lobby, and I frantically wrote down everything I could remember from our conversation.

I was in a bit of a whirlwind when John and I reunited. He informed me that he made us a reservation at Oniku Karyu for a wagyu beef kaiseki dinner. Over two large bottles of sake and ten mouthwatering courses featuring hand selected A4 and A5 rank Japanese Black beef, John and I indulged in our final meal of the trip. I debriefed him on my meeting with Mr. Easley and his concealed way of talking about Betty. We looked back on the last six days with a combination of pride and perplexity–a familiar feeling that both of us had come to know during our respective time with Betty Davis.