Day 4: Tuesday, March 5th

At dawn, I woke up in Kawaguchiko and peeled back the heavy curtains in my hotel room to greet Mount Fuji. I was surprised to see the crystal-clear view of the sacred mountain that was there yesterday during our ceremony for Betty was now replaced with a dense, thick fog that enveloped the entire landscape. After spending six years with Betty at the end of her life, her precision detail to nature’s timing eventually permeated my thought process and how I moved in the world. I couldn’t help but smile and feel a gentle nudge from the universe letting me know we were right on time.

With several hours to spare before our train back to Tokyo, I dressed myself in the traditional yukata provided by the hotel and made my way downstairs to the onsen. At 6 am, I was the only person in the hotel enjoying the hot spring water filtered directly from Lake Kawaguchiko. I relished in its tranquility. It was Betty who taught me how to appreciate silence, to harness its power for intellectual and emotional cleansing. We would often sit for extended periods in silence, at her request, embracing the stillness of the moment. After soaking in the health-boosting mineral water for two hours, I readied my mind and body to re-enter the noise of the outside world—and to continue our journey in retracing Betty Davis’s final steps as a working musician in Japan.

…

Back in Tokyo, we were due to meet composer Shigeru Umebayashi for dinner and then head to the Crocodile Club and meet owner Tetsuya Nishi, who’s been booking musical acts (including Betty Davis and the Arakawa Band) since the 1970s. As I prepared for our evening, I returned to my playlist and began listening to “Yumeji’s Theme,” from the 2000 Chinese film In The Mood For Love.

I had heard about its composer, Shigeru Umebayashi–or, as Betty referred to him, Ume–for several years before Betty passed away. While living in Japan, Betty, as she had been doing her entire career, set out to make connections. She was introduced to Ume who, at the time, was playing bass in Japan's new wave/post-punk band EX, which was active from 1978 until 1985. Nothing transpired from their meeting in 1983 besides a few instances of creative sharing where Betty sang him some new song ideas. However, forty years later, the two would find their timing with a musical collaboration.

Those close to Betty knew she was actively writing music during the last years of her life. Her notebooks were full of lyrics, and her 1996 Sony cassette tape recorder held hours of her voice mimicking various instrumental parts for her arrangements. She had been working on a song called “Two Hands” since I met her back in 2016, although it wasn’t until Ume came back into her life that the song really came alive.

After leaving the underground Japanese rock scene, Ume began scoring films and quickly rose to international success in both the Japanese and Chinese film industries. Once the two musicians reconnected, they began writing letters and engaging in a lively correspondence. Betty would record her voice on tape singing the melody of “Two Hands,” send it to Ume, and then he would arrange different compositions around it. It was a collaborative experience that Betty thrived on. Through this creative back and forth with an esteemed musician such as Ume, she was able to spend her final years doing what she loved most: songwriting.

We arrived at Bikkuri Sushi Ebisu to meet the internationally renowned film composer along with his manager and production assistant, Kumiko Sekiguchi. Over much sashimi and beer, we soaked up every word from Ume about his distant memories of Betty struggling to find gigs in Japan while living alone in a YWCA. Her determination and passion to stay in the game as a free agent was evident to him, as were her lack of resources. It wasn’t soon after Betty met Ume that she left Japan.

Several decades would pass without any contact, but Betty and Ume made a lasting impression on each other. I can still hear Betty’s overjoyed voice when she told me that Ume had called her, and she pitched him her new song. There was absolutely no reason Ume–a recent Lifetime Achievement Award winner from the Rome Film Festival–needed to engage in this musical collaboration other than for his profound belief in his old friend’s talent and his comfort in knowing she was not only alive and healthy… but inspired!

As of this writing, Betty’s inner circle and Ume’s team are the only ones who have heard “Two Hands,” but it was Betty’s wish to share it with the world, and both Ume and Light in the Attic are eager to make that wish a reality.

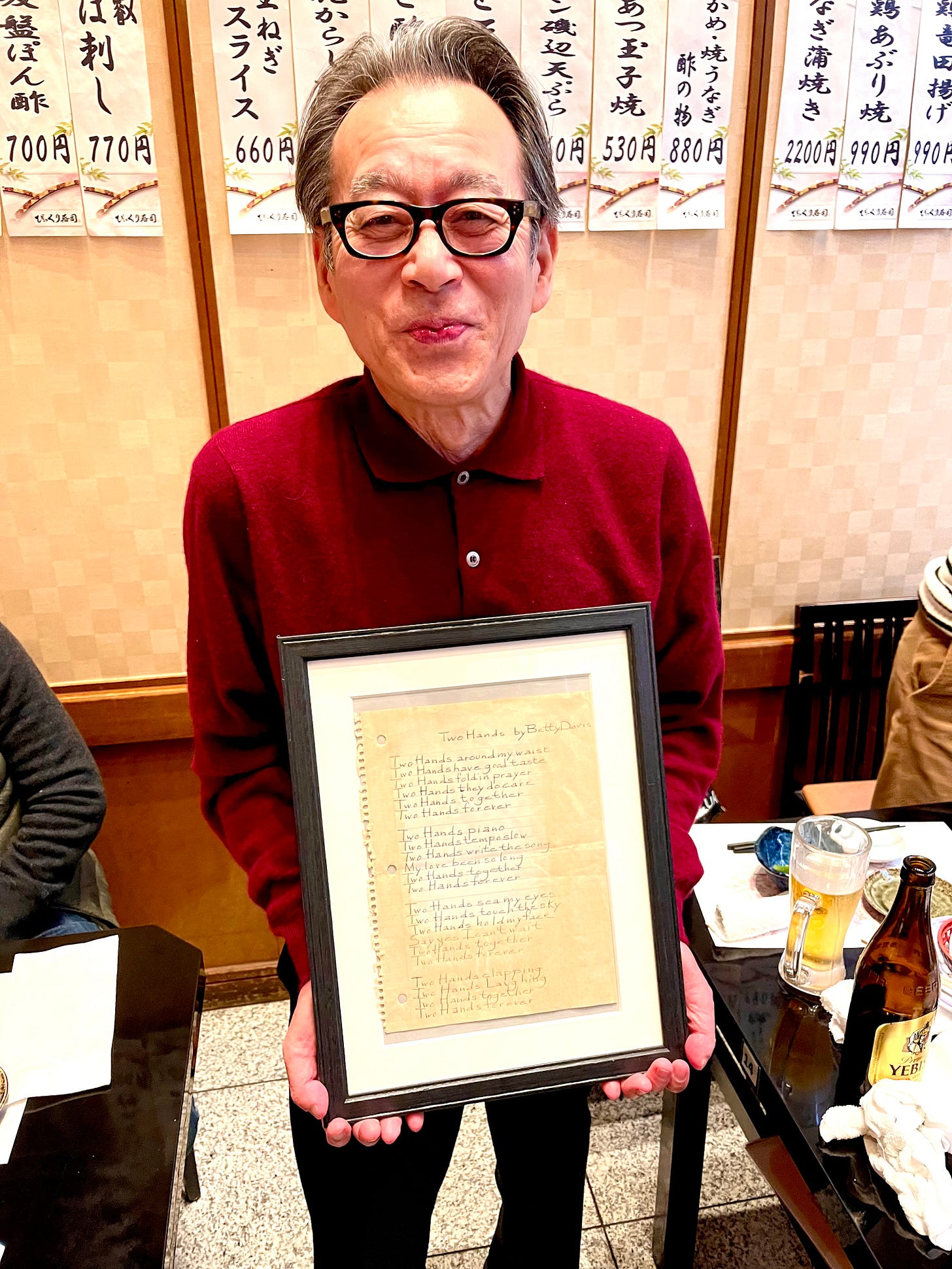

At dinner, Ume brought a framed copy of the original handwritten lyrics that Betty sent him. His pride for this object was palpable. As we readied to leave, he presented a massive collection of papers and envelopes. “These are all the letters Betty wrote me, I saved them all,” he said as he gently handed them to me. I was overwhelmed with gratitude for the care he took in preserving this correspondence, and honored by the trust he placed in me, so that I may expand my archive and continue to document Betty’s story.

We said our goodbyes and told him we were heading to the Crocodile Club.

“Ahhh,” he laughed. “Good times… Is Mr. Nishi still there?”

…

The cab dropped us off in the rain in front of a sign that read “Crocodile Club,” and we followed the stairs leading down to the basement venue. As I entered the club, I thought of Betty descending the same stairs and wondered if it ever occurred to her–out of anxiety or fear, perhaps–that she may be entering the last club she would ever perform in. How could she have known when she opened that door forty-one years ago that she was opening a portal of future research into her life and career–a life and career that would be talked about as pioneering many, many years later.

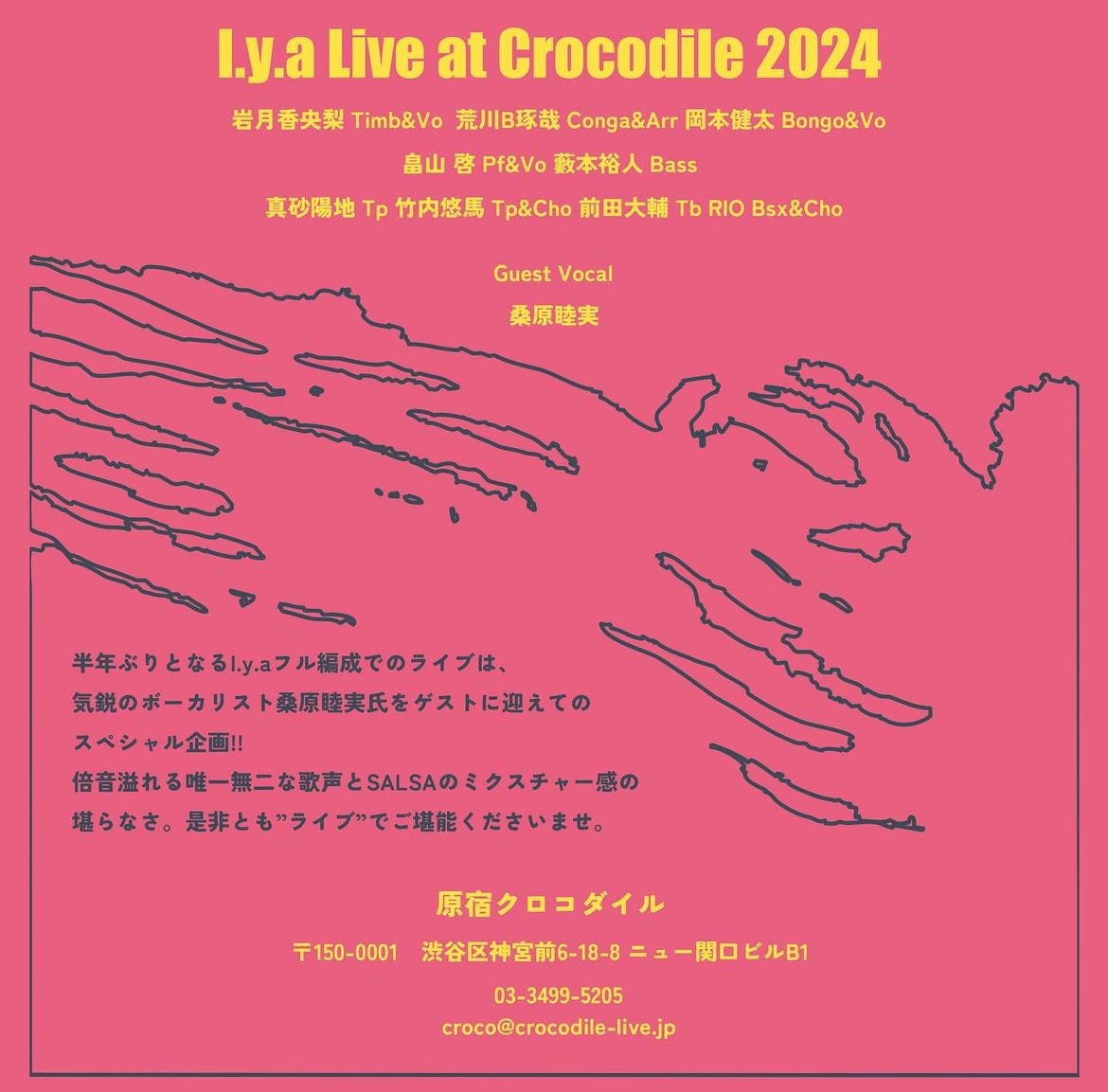

We were all prepared to catch whatever act was performing that night. We were not prepared, however, to have our faces melted by some of the hardest live salsa music we have ever heard! When we arrived, I.y.a., a twelve-piece Japanese salsa band led by timbales player Kaori Iwatsuki, was fully warmed up and mid-way through their set. The polyrhythmic intensity, driven by the clave beat, made it impossible to stand still. Their deep reverence for New York City salsa resulted in a true mastery of the Afro-Latinx genre. New Yorker Damon [Smith] said to me in astonishment: “I’d love to see this group perform in front of a Harlem audience.”

I couldn’t imagine the band sounding better. That is, until guest vocalist, Mutsumi Kuwahara, took the mic. Her booming contralto voice went toe to toe with the energy of the band. The soulfulness of her delivery, the musicality of her phrasing, and her command of the stage left us uninhibited–dancing, drinking, and hollering as if the Crocodile was our neighborhood club.

At the end of their set, we gathered ourselves, albeit it more intoxicated and sweaty then when we arrived, in continuation of the mission: Mr. Nishi. In the midst of my dancing, I noticed an older man behind the audio booth giving a very low-key, “Captain-of-the-ship” vibe. We approached him with our trusty translator, Greg [Gouty].

Mr. Nishi shared his memories of Betty stomping around his stage with the Arakawa Band backing her up. When I asked him what the audience thought of her performance, he nodded and said: “Very strong performance. Very sexy. The audience loved blues and rock, so Betty was a unique act.”

Like all the friends and bandmates we’d spoken with up until that point, Mr. Nishi noted that Betty seemed to be struggling to make enough money as a musician to live in Japan on her own,with no support from a label or manager. When asked how Betty ended her time at the Crocodile Club, Mr. Nishi said she simply did not show up for a gig.

By the end of winter in 1983, Betty Davis returned back home to Pittsburgh–seemingly out of necessity–and quietly adjusted to a life away from performance and the public eye all together.

Before we left, I looked back at the stage one last time. I couldn’t help but feel somewhat sad knowing how Betty had to leave Tokyo. Going across the world with a group of friends, a translator, and all the bells and whistles of modern technology was intimidating in and of itself. But Betty had none of these things–only her talent, tenacity, and unwavering commitment to artistic control.

No one gave this final stage to Betty; she took it. And, with that thought, my distress passed, and I left the club in awe of the woman I had the honor to know; in awe of a moment in music non-history that was coming more clearly into focus: Betty Davis’s final bow.

Live at The Crocodile Club. Tokyo. 1983.

I have definitely been missing out in music. Again beautifully written.